By Christian Glennie, Healthcare Analyst, Edison Group

There is a clear and compelling rationale for incorporating a biomarker programme, with the aim of identifying companion diagnostics (CDx), into the development of novel drugs. The ability to identify patients most likely to respond to, or better tolerate, a given agent will improve the chances of clinical success, regulatory approval and reimbursement from healthcare payers. Herceptin, an anti-HER2

antibody, was the flagship for the field, approved in 1998 to treat breast cancers that overexpress the HER2 protein, identified by a diagnostic assay.

Yet it is only recently that the rate of development and regulatory approvals for targeted agent/diagnostic combinations has accelerated. And despite recent trends and the persuasive clinical/economic arguments, we suggest that investors are yet to properly reward companies with active biomarker/diagnostics programmes. In theory a premium should be paid for companies with a clear CDx

strategy, but we expect this will only occur once the full benefits of improving clinical success rates, drug price and market penetration become more apparent.

Current trends in perspective

According to PharmGKB, a pharmacogenomics (PGx) database that collates PGx data from FDA and EMA drug labels, there are currently 150 approved drugs that have pharmacogenomic biomarker information in their labels.

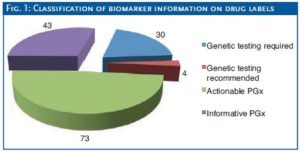

The importance and relevance of the PGx data is variable and can be stratified into four categories: genetic testing required (must be conducted before using drug), genetic testing recommended (should be considered), actionable PGx (highlights variants known to impact

efficacy/toxicity/dose), and informative PGx (highlights relevant variants but without evidence of impact on efficacy/toxicity).

The number of drugs which require genetic testing prior to administration is a relatively small proportion, applying

to just 30 of the 150 identified drugs. The vast majority of PGx information on drug labels is either ‘actionable’ or ‘informative’ (Fig. 1).

Unsurprisingly, of the 30 drugs that require genetic testing, 23 are cancer agents, reflecting the genetic basis for the disease and the relative ease in identifying a causative mutation. Of these, the majority (19) have been approved by the FDA since 2000. Over the same

period, a total of 59 cancer drugs were FDA-approved, meaning that almost one-third has a requirement for genetic testing. Exhibit 2 summarises this data, and highlights the increasing proportion of companion diagnostics required for cancer drugs, a trend that we expect to continue to rise in the coming years.

The supporting evidence is strong…

Recent cancer drug approvals in 2013 highlight the inherent value of the CDx approach. Trametinib (Mekinist) and dabrafenib (Tafinlar) were approved for metastatic melanoma, in patients with a BRAF mutation. In 2011, vemurafenib (Zelboraf) was approved for melanoma

with the same mutation, meaning that after decades of research failures and lack of treatment options, there are multiple targeted agents available. Likewise the recent approvals of new agents for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a notoriously head-to-treat cancer:

afatinib (Gilotrif) for patients with a specific type of EGFRmutation, and crizotinib (Xalkori) for patients with ALK-positive NSCLC.

Outside the oncology arena, identifying suitable biomarkers and developing companion diagnostics is more of a challenge and protein biomarkers will also be required. The genetically-based, rare, orphan drug indications are well-suited for CDx, and the approval in 2012 of ivacaftor (Kalydeco) for cystic fibrosis patients with a CFTR gene mutation, is a recent example. We expect the huge investment

made in rare disease R&D over the last ten years in particular, to start to pay off with approvals for new personalised medicines.

…although there is some way to go…

The proportion of novel drugs approved with a CDx is still relatively modest, and while we acknowledge the challenges in identifying suitable biomarkers, there remains a tangible need for greater investment in CDx programmes. These initiatives also need to be instigated early in drug development and be more proactive, with prospective CDx analysis in clinical trials, rather than retrospective assessment which is not typically acceptable to the regulators.

As for the diagnostics companies, there is a real challenge in addressing the valuation imbalance between their CDx agents (typically costing 100s USD) and the associated drug (often 10,000s USD). It is interesting to note that the FDA’s list of 19 approved CDxs is dominated by large players (Abbott, bioMérieux, Dako, Qiagen, Roche), and emerging companies appear to be acquired more often than

similar-stage biotechs. This suggests that valuations of small diagnostics companies remain relatively low, particularly compared to booming biotech valuations today. The trick therefore is to identify noveland proprietary markers for disease and/or drug targets, which drug companies may be willing to license under more classical and lucrative terms (upfront fees/milestones/royalties).

…before investor rewards flow

As such, the CDx field, despite the apparently compelling investment case, has some way to go before the inclusion of a CDx programme influences standard valuation metrics of market size, drug price and penetration rates. A body of evidence therefore needs to build up that shows that clinical, regulatory and reimbursement success is improved with CDx.

Conclusion

We envisage this will emerge in the coming years, and anticipate that investors will then lower their riskadjustments for products with a CDx programme, or companies with a clear commitment to discovering and developing a biomarker programme. Ultimately, investors,

regulators and healthcare payers will reward companies that are the most successful at implementing a comprehensive CDx strategy.

Autor/Autorin

Die GoingPublic Redaktion informiert über alle Börsengänge, Being Public, Investor Relations, Tax & Legal, Themen und Trends rund um die Hauptversammlung sowie Technologie – Finanzierung – Investment in den Lebenswissenschaften.